ISBN 0870714821 (hardcover)

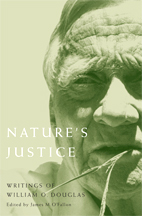

Nature's Justice

James M. O'Fallon

As the longest serving Justice in the history of the U.S. Supreme Court, William O. Douglas was known for writing a host of dissenting opinions. He was also a prolific writer off the bench, a man whose work was as much concerned with nature as with law.

This collection brings together writings that represent the wide range of Douglas's interests. It includes selections from his autobiographical and political books, and opinions from landmark cases—all reflecting not only his love of justice but also his roots in the Northwest and his lifelong commitment to the environment.

Several selections from Douglas's first book Of Men and Mountains portray his abiding love of the outdoors—particularly the Northern Cascades—and the rugged people who live there. These personal writings warmly recall events of his youth and celebrate the power of the mountains to renew the human spirit.

Other selections evoke Douglas's professional activities: as a New Deal insider and Supreme Court Justice, a champion of civil liberties and the rights of minorities, a strong internationalist, and an unflagging supporter of environmental issues. These latter writings include passages from My Wilderness and his dissenting opinion in Sierra Club v. Morton arguing that trees have legal standing to bring lawsuits.

These writings demonstrate that Douglas never shied from controversy—whether over interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment or the choice between flies and bait for trout fishing—and offer inspiration for both environmentalists and all who yearn for a more just society. Whether extolling the joys of the wild or defending the rights of citizens, Douglas shows in this work that he truly was Nature's Justice—and one of a kind.

Of related interest: The Environmental Justice: William O. Douglas and American Conservation

About the author

James M. O'Fallon is the Frank Nash Professor of Law at University of Oregon School of Law. He lives in Eugene, Oregon.

Read more about this author

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Part One

At Home in the Mountains

"Foreword" (from Of Men and Mountains, 1950)

"The Cascades" (from Of Men and Mountains, 1950)

"Sagebrush and Lava Rock" (from Of Men and Mountains, 1950)

"Coming of Age in Yakima" (from Go East, Young Man, 1974)

"Fly vs. Bait" (from Of Men and Mountains, 1950)

"Roy Schaeffer" (from Of Men and Mountains, 1950)

Part Two

New Deal Judge

"The New Deal" (from Go East, Young Man, 1974)

"Brandeis and Black" (from Go East, Young Man, 1974)

"Contending Schools of Thought" (from The Court Years, 1980)

"Franklin D. Roosevelt" (from The Court Years, 1980)

Part Three

Civil Libertarian

"Mr. Lincoln and the Negroes" (Excerpt. 1963)

Free Speech Cases

"Terminiello"

"Dennis"

"Beauharnais"

"The Right to Be Let Alone" (from The Right of the People, 1958)

Griswold v. Connecticut

"Points of Rebellion" (excerpt, 1970)

Part Four

Internationalist

"Vietnam--Nation in Disintegration" (fromNorth of Malaya, 1953)

"Vietnam" (from The Court Years, 1980)

Part Five

Conservationist

"Pacific Beach" (from My Wilderness, 1960)

"Middle Fork of the Salmon" (from My Wilderness, 1960)

Sierra Club V. Morton

Selected Bibliography

Index

Cause and effect in the formation of human personality is an elusive matter. Nonetheless, one can say with confidence that the marks of his youth in the Northwest stayed with Justice William O. Douglas for life. His love of the mountains and the outdoors were only the most obvious of those marks. His fierce independence, his concern for outsiders, his suspicion of concentrated power, all have roots in childhood experience.

Douglas was born in the tiny town of Maine, Minnesota, on October 15, 1898, to Julia Fisk Douglas and the Reverend William Douglas, a Presbyterian minister. The family moved from Minnesota to Estrella in Southern California when Douglas was three, hoping to find relief from physical problems that afflicted Reverend Douglas, and then moved again, to Cleveland, Washington, less than two years later. The moves did not resolve the health problems, and Reverend Douglas died after an ulcer operation in 1904.

After her husband's death, Julia Douglas moved her family--William, his older sister Martha, and his younger brother Arthur--a few miles north to Yakima, where her sister lived. Yakima would be Douglas's home until he went away, though not too far, to Whitman College in Walla Walla when he was 18.

Julia Douglas used some of the proceeds of her husband's life insurance policy to build a modest house for her family across the alley from the Columbia Grade School. She invested the rest in an irrigation project, promoted by a local lawyer, which failed, leaving the family in a state of poverty that would have important consequences for Douglas's childhood. Most significantly, it dictated that the children would work, at whatever jobs or tasks they could find, to help[ support the family. From the age of seven, when he would prowl the byways of Yakima looking for scrap iron or burlap sacks that he could sell for a few pennies, Douglas was gainfully engaged. He washed windows and swept out stores, picked fruit and harvested wheat. He worked his way through college at Whitman, and through Columbia Law School.

The experience of growing up poor left Douglas with an acute sense of class distinctions in American society, though he denied their significance on himself. In a telling passage in his autobiography he said, "We never felt sorry for ourselves; we never felt underprivileged. Class distinctions were nonexistent in our eyes: we went to the same schools as the elite; we competed for grades with them and usually won." yet in the paragraph he wrote "Because of our poverty, we did occasionally feel that we were born 'on the wrong side of the railroad tracks.'"

Douglas wrote with feeling of the circumstances of junk collectors in Washington, D.C., migrant workers and "Wobblies," hoboes and prostitutes. He rode the rails to get from job to job around Eastern Washington, and even to get to New York for law school. He recalled having been hired by one of the pillars of Yakima society to act as a "stool pigeon" in the red light district, attempting to buy liquor and inviting solicitation, in order to facilitate prosecutions. The experience left him with an abiding sense of the hypocrisy of the elite, who would hire him to do a job that they would not set their own children to do. Douglas would spend most of his adult life among the elite, but in important ways he would always remain an outsider.

As an infant, Douglas contracted polio. The attending physician told Julia that William might not walk again, and would probably be dead by 40. The only therapy he could recommend was regular massage of the boy's legs with salt water. For weeks, Douglas's mother followed a regimen of soaking and rubbing his legs every two hours. Eventually, he did regain the use of his legs, and learned again to walk, but his legs were spindly, and became the object of jibes from his schoolmates when he was older. Douglas was never a gregarious person, and he attributed his preference for being alone to a sense of physical inferiority that had separated him from others of his age as a young teen.

Attempting to overcome the lingering physical effects of the polio, Douglas eventually turned to walking the foothills around Yakima to build strength and stamina in his legs. It worked, and started him on a lifetime of hiking that included treks through the himalayas and a famous walk down the C&O Canal in 1954, to protest plans to turn the canal path into a parkway.

What began as a discipline for building strength soon was transformed into an abiding love for the outdoors. A powerful sense of that attachment is conveyed by a passage from his autobiography.

Another trip into those hills marked a turning point in my life. It was April and the valley below was in bloom, lush and content with fruit blossoms. Then came a sudden storm, splattering rain in the lower valley and shooting tongues of lightning along the ridges across from me. As the weather cleared, Adams and Rainier stood forth in power and beauty, monarchs to every peak in their range.

Away from the town, in the opposite direction from its comforts, the backbone of the Cascades was clear against the western sky, the slopes and ravines dark blue in the afternoon sun. The distant ridges and canyons seemed soft and friendly. They appeared to hold untold mysteries and to contain solitude many times more profound than that of the barren ridge on which I stood. They offered streams and valleys and peaks to explore, snow fields and glaciers to conquer, wild animals to know. That afternoon I felt that the high mountains in the distance were extending to me an invitation to get acquainted with them, to tramp their trails and sleep in their high basins.

My heart filled with joy, for I knew I could accept the invitation. I would have legs and lungs equal to it.

Julia Douglas adhered to the familiar notion that education was the way to success. She inculcated that view in her children, who had both the natural talent and the persistence to make it come true. Martha became a successful businesswoman. Arthur followed Bill to Columbia Law School, and went on to a Wall Street law firm, to the General Counsel's office for the Statler Corporation, and eventually to the presidency of the Statler Hotel Chain. But even in the context of his accomplished set of siblings, Bill Douglas stood out. His biographer recounts an incident when a teacher remarked to Julia "Both Martha and Orville are good students, but Orville has the more unusual mind." Douglas would gather his share of detractors, perhaps more than his share, but none seemed to doubt the special quality of his mind. Indeed, his brilliance may have been the source of some of his problems, as well as the font of his success. The pace of his life suggests someone who was easily bored, and he had little patience for hose who had to struggle to understand what came to him almost intuitively.

Douglas thrived in the competitive forum of high school debate when physical limits precluded athletic achievement--though he did play on the basketball team. He completed his preparatory work as class valedictorian, which earned him a full tuition scholarship to Whitman College in Walla Walla. He paid his way (including twenty dollars a month sent home) by working two or three jobs at a time, while sustaining a record of academic excellence.

He joined the army early in World War I, when he was still a student, but after basic training was sent back to the ROTC unit at Whitman, where he remained from the duration. He joined Beta Theta Pi and clearly enjoyed the comaraderie of that association, though in later life he would conclude that the clannishness of college fraternities was a handicap. It was not a handicap when it saved him from a night on the street after he arrived in New York dirty and broke to begin law school. Douglas was about to be turned away from the Beta club in New York by a skeptical clerk; an old Whitman friend fortuitously intervened and vouched for him, and provided a loan to get him through his first days in the big city.

Douglas spent the first two years after graduation from Whitman as a high school teacher and debate coach at Yakima High School. He hoped to go to graduate school, either in English literature or in law, but did not have the financial means. He finally decided on law school, and was led to Columbia by James Donald, a Yakima attorney and Columbia graduate, who informed him that it would be possible to find work to support him through his course of studies.

The journey to New York was an adventure in itself. He signed on to escort a shipment of two thousand sheep by rail from Yakima to Minneapolis. He rode the caboose for nearly two weeks, enduring a rail strike, rain and dust storms, hunger, and lack of sleep. After delivering his wooly charges to a broker in Minneapolis, he hopped a freight for New York, but was tossed from the train in Chicago. Different versions of the story disagree on whether he completed his trip to New York on another freight, or in a coach paid for by money wired from his brother. In any event, Douglas arrived in New York dirty broke, but undaunted.

Douglas spent his first day at the Columbia Law School in a desperate effort to come up with the money to pay his tuition. Dean Harlan Fiske Stone, who would later be douglas's colleague on the Supreme Court, suggested that he should find a job and reapply to the school when he had saved the tuition. In a last-ditch attempt to solve the problem, Douglas responded to an ad for a third-year student to assist in drafting a correspondence course in commercial law. He talked his way into the job--he did not mention to the employer that he was a beginning student--and received an advance that allowed him to enter the law school.

He continued to work during his three years at Columbia, primarily as a tutor for students trying to gain admission to Ivy League colleges. Douglas cited the two criteria for his services--that the student be rich and stupid. He was well compensated for his work. By the summer of his second year, he had saved enough to return to the West, where he married Mildred Riddle at her parents home in La Grande, Oregon. They had met while both were teaching at Yakima High School. They spent their honeymoon camping, fishing, and riding in the Wallowa mountains of eastern Oregon. Douglas was broke by the time they got back to New York for his last year at Columbia, but he continued tutoring and Mildred got a teaching job.

High academic achievement was the norm for Douglas, and he continued in that pattern at Columbia, and he was selected tot he law review staff at the end of his first year, indicating that he stood near the top of his class. During his last two years, he worked as a student assistant for Professor Underhill Moore. He helped Moore revise his casebook on commercial law, and in his final year worked with Moore on a study of the marketing practices of the portland cement industry, in anticipation of a possible antitrust investigation.

Douglas described Moore as having a mind with "a cutting edge, sharper than any other." Underhill Moore was one of the most important figures of a movement in legal thought that came to be identified as "American Legal Realism." The Realists criticized traditional legal thought as overly formal, and out of touch with the real world. They were inclined toward empirical study rather than looking to legal precedents, and many of them promoted work in other disciplines, such as psychology, sociology, and economics, as essential to an adequate understanding of how law functions in society. Moore was probably the most committed and successful of the empiricists among the Realists, conducting studies that examined the influence of local banking practices on legal outcomes, and sitting for hours on a sidewalk in New Haven, observing the parking behavior of the residents. It is not difficult to find the influence of this commitment to fact in Douglas's later work as a judge.

among Douglas's instructors at Columbia were other men of noted achievement, including, of course, Harlan Fiske Stone, later Douglas's Chief Justice on the Supreme Court. Herman Oliphant was another of the major figures in the Legal Realist movement. Thomas Reed Powell was for years the most prominent academic critic of the Supreme Court; he gave Douglas a C in constitutional law. Richard Powell became the country's leading scholar on the law of property. Harold Medina, who taught Douglas the intricacies of New York practice, would later sit as the trial judge in Dennis v. United States. In this case, eleven leaders of the Communist Party of America were convicted of violations of the Smith Act, which made it a crime to advocate the violent overthrow of the government, even if no further steps were taken. Douglas would write one of his more famous dissents, insisting that the defendants be judged on the basis of what they had done--the facts--rather than on speculation about what they might do.

Douglas graduated second in his class. That minor slip cost him a cherished opportunity. Harlan Stone had left the deanship in 1923. After a brief period in private practice, Stone was appointed Attorney General of the United States, and shortly thereafter was appointed to the Supreme Court. Douglas was passed over for an appointment as Stone's law clerk in favor of Albert McCormack, who had finished first in the class.

Douglas had a position with Grant Bond in Walla Walla to go to, but he could not go without first testing himself against the demands of a big city law practice. He secured a position with the prominent Wall Street firm of Cravath, deGersdorff, Swaine, and Wood. At the same time, the Columbia faculty offered him the opportunity to teach three courses as an adjunct member of the faculty. The work schedule at his firm was notoriously demanding. Sixteen hour days preparing for and teaching a class each morning at 8:00.

Douglas's work at the firm was the legal equivalent of latrine duty in the army. He and one other junior associate, John McCloy, were assigned to work with Donald C. Swatland, a demanding senior associate who was coordinating work on the reorganization of the Chicago, Milwaukee " St. Paul Railroad. The reorganization became a major target of critics bemoaning the role of law firms and corporate banks in taking advantage of the problems of struggling railroads. The Cravath firm made $450,000 on the St. Paul case. A sense of the significance of that figure can be gained by comparing it to Douglas's salary of $1,800.

Less than a year after starting with Cravath, Douglas was having health problems and was not enjoying himself; he decided to return to the West and his beloved mountains. He took up practice in Yakima, in the office of James Cull--the lawyer who had talked Douglas's mother into the ill-fated investment that had cost her the family nest egg. But the reality of small town practice, both financially and intellectually, soon set in. After only a few months, he was back at Cravath and teaching his Columbia courses. In the spring of 1927 he was offered a full-time teaching position at Columbia, which he accepted.

The next decade of William O. Douglas's life can fairly be characterized as meteoric. He began his full-time teaching career on the ever of his twenty-ninth birthday. He would celebrate his forty-first birthday as an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court. In the interim, he would serve on the faculties of Columbia and Yale, turn down appointment at the University of Chicago, teach courses at the Harvard Business School, and serve as a member and then Chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission. His scholarly production between 1929 and 1934 included five casebooks and more than a dozen articles. It was a record that reflected both his great intellectual talents and his capacity for prolonged hard work.

Douglas began his tenure at Columbia at a time of ferment in legal education and turmoil within the Columbia faculty. The Legal Realists were making waves, and those waves were breaking hard in upper Manhattan. Douglas joined forces with Underhill Moore and other colleagues to push for a complete and systematic restructuring of the curriculum. There was broad agreement across the faculty that reform was in order, but there was a basic schismy. One group wished to transform the basic mission of the law school, subordinating the training of prospective lawyers to a primarily research mission. The others, perhaps with a more realistic appreciation of how their salaries were paid, wanted to bring change within the traditional context of a school devoted to the education of future lawyers.

Douglas aligned himself with the first group, though perhaps not as forcefully as his retrospective account in his autobiography suggests. The ensuing battle focussed on the question of who would be appointed Dean. Oliphant was the Realists' candidate, while Young B. Smith was the choice of the more traditional faculty. According to Douglas's autobiography, the appointment of Smith, whom he characterized as "the antithesis of what we wanted" and "utterly opposed to what we were trying to do," precipitated his resignation from the faculty. Another account suggests that Douglas did not formally resign from Columbia, though he accepted a position at Yale. In the fall of 1928 Douglas moved to New Haven and began his tenure at Yale.

Here Douglas found compatible associates in Thurman Arnold, Wesley Sturges, and Dean Robert Hutchins. Arnold too, had come from the West, having grown up in Wyoming, though as the son of a prosperous Laramie lawyer, he had not shared the financial hardship that was Douglas's lot. Douglas described Arnold as "an unorthodox, nonconformist, unpredictable man with an extremely sharp mind and an unusual wit. He was a brilliant lawyer and a wild and wonderful companion." The stories of their companionship include an evening of driving on the sidewalks of New Haven, after Arnold's wife threw him out for showing up late and intoxicated for a dinner party she was hosting. Arnold recounted a story of a prank that Douglas played on him. Arnold received a note from a woman named Yvonne, claiming to have met him at a party, and lavishing flattery on him. When he called the number given on the note and asked for Yvonne, he was informed that he had called the morgue.

Douglas and Arnold worked together on a report for the national Commission on Law Observance and Enforcement, for which they collected and correlated massive amounts of information about the functioning of courts. On Arnold's account, "We ... proceeded to count everything that had happened in courts in Connecticut ... we counted everything ... that we or anyone else could think of ... the result was the most fascinating body of legal statistics that has been collected in this century. They had only one flaw. Nobody then and nobody yet has ever been able to think of what to do with them." Some years later, Douglas reminded Arnold that he still had ninety-nine of the hundred copies of the report that he had ordered for himself. Arnold responded that the still had his full one hundred.

Douglas's academic career was as far removed intellectually from his future fame as a civil libertarian as New Haven was from Yakima. He made his scholarly mark studying business organizations, corporate finance, and bankruptcy. True to the empiricist roots of legal realist thought, Douglas undertook extensive field studies of business failures, hoping to gain information upon which legislators could base more enlightened bankruptcy regulation.

Douglas and his former Columbia classmate, Carrol Shanks, produced casebooks on the law of corporate reorganization, business finance, and business management. They sought to bring the insights of other disciplines, including economics and sociology, to bear in the law school classroom--an innovation at a time when the standard casebook was little more than its name implied, a collection of highly edited appellate court case reports. His scholarship earned him the designation, by his former dean, Robert M. Hutchins, now at Chicago and hoping to persuade Douglas to join him there, as the nation's outstanding professor of law. To keep him, Yale jumped him ahead of his colleagues in salary, and awarded him its most prestigious chair, as Sterling Professor of law.

It was, of course, a propitious time to be studying business failures. Following the stock market crash in 1929, the economic fortunes of the country sank into the Great Depression. With the election of Franklin Delano Roosevelt to the presidency in 1933, it soon became apparent that government would become much more aggressively involved in seeking solutions to economic problems. Bright young men began migrating from the faculties of elite universities to the administrative agencies of Washington, D.C. Congress passed an act in 1933, giving regulatory authority over the sale of securities to the Federal Trade Commission. The Securities Exchange Act of 1934 required the registration of all securities traded on an exchange, such as the New York Stock Exchange, and created the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) to oversee the operation of the law.

Douglas had been actively pursuing an opportunity to join the parade to washington for two years, when he was offered the opportunity to direct a study for the SEC. While it was not all that he wanted--he would continue to teach at Yale while directing the study, thus becoming a regular on the train between New Haven and Washington--it was a step in the right direction. Little more than a year after the SEC got underway, Joseph P. Kennedy stepped down from its chairmanship. During that year, Douglas had established a strong relationship with Kennedy, which would continue and would eventually encompass Kennedy's sons John and Robert. James Landis, a member of the Commission, was promoted to the chairmanship, and Douglas was appointed to fill Landis's position in January 1936.

Douglas Quickly became an outspoken critic of the Wall Street establishment, and a defender of New Deal economic policies. When Landis resigned to accept the deanship of Harvard Law School in September 1937, Douglas was appointed to chair the SEC. He had by then become a nationally prominent figure, profiled in Newsweek as a brilliant scholar and remarkable man. His appointment to the chairmanship was strongly opposed by the leaders of the securities industry, but that very opposition worked in his favor in the president's consideration. Douglas's tenure was dominated by a struggle with the leadership of the New York Stock Exchange. He insisted that the "insiders club" method of management which had controlled the exchange since its establishment should give way to a paid professional president, not a member of the exchange, and a board of directors including representatives of the public interest. The battle was intense, but Douglas finally won out in the aftermath of public exposure of the frauds and embezzlements of Richard Whitney, long the leading force in the management of the exchange.

In March 1939, Douglas was nominated to replace retiring Justice Louis Brandeis on the Supreme Court. Brandeis had been a highly visible advocate of the public interest, particularly with regard to business regulation, prior to his appointment to the Court, and Douglas had long been an admirer. Douglas's nomination was confirmed by the Senate with only token opposition; upon taking the oath of office he became the second youngest Justice in the history of the Court. He would retire in 1975. the longest serving justice in history.

Douglas joined a Court that was in rapid transition. In 1935 and 1936, the Court had handed down a number of decisions invalidating President Roosevelt's economic initiatives, generally on the ground that the programs exceeded the constitutional powers of the federal government. The Court was bound to a view that limited federal power in the interest of preserving the independent authority of the states, notwithstanding the fact that the states were incapable of addressing the nationwide distress of a highly integrated economy.

After his landslide reelection in 1936, Roosevelt proposed a plan for reorganization of the Court that, not incidentally, would provide him with the opportunity to make a number of appointments; obviously, he would select justices whose views of federal authority would accommodate his New Deal programs. The plan, quickly dubbed the "court packing" plan, would have provided that if a justice reached the age of seventy and did not retire, the president could appoint an additional justice of the Court. At the time of the proposal, six justices were over seventy.

The plan met with immediate disapproval from a variety of quarters, including some staunch supporters of the New Deal, but Roosevelt persisted in pushing it. Whether in response to the political attack represented by the plan, or because of a rethinking of basic constitutional principles, the Supreme Court began to shift towards a view of constitutional power that permitted federal regulation of activities that had previously been held to be of exclusive state concern. Most significantly, the Court sustained the National Labor Relations Act and the Social Security Act, two cornerstones of the New Deal.

Though the court packing plan failed legislatively, a number of the most conservative justices retired. Roosevelt's first appointment was Hugo Black, a Senator from Alabama and stalwart champion of the New Deal. Stanley Reed, who as Solicitor General had argued for the government in a number of the early New Deal cases, was appointed to replace George Sutherland, one of the most conservative members of the Court. Benjamin Cardozo, a relatively moderate justice, died in office and was replaced by Felix Frankfurter, who, as a Harvard professor and close associate of Justice Brandeis, had been deeply involved in the politics of the Roosevelt presidency from the outset. Shortly after Douglas's appointment, Pierce Butler, another conservative, retired, to be replaced by the very liberal Frank Murphy. Thus by 1940 Roosevelt had appointed a majority of the sitting justices of the Supreme Court. He had, in his own words, lost the battle, but won the war.

Frankfurter had a hard time leaving his professorial ways behind him. In fact, he did not even try. He assumed that a lifetime of teaching and writing about the Constitution would give him a leadership position among the recent appointees; only Douglas was a scholar, and his work had had little to do with the Constitution. However, the combination of a rankling personal style--the accomplished men of the Court did not take kindly to being lectured--and differences of opinion soon led to a breakdowns of relations between Frankfurter and his fellow Roosevelt appointees. Douglas's biographer traces the breakdown to two cases involving a requirement that schoolchildren begin the day with the pledge of allegiance to the flag.

In the case of Minersville School District v. Gobitis Frankfurter wrote for eight members of the Court, sustaining the pledge requirement against a challenge by Jehovah's Witnesses, who claimed that the compelled recitation violated their religious scruples and thus the First Amendment guarantee of free exercise of religion. White acknowledging the gravity of the issue, Frankfurter wrote that the state's legitimate interest in inculcating patriotism outweighed the infringement of the Witnesses' religious freedom. Only Douglas's old dean, Justice Harlan F. Stone, dissented from the ruling.

In the months following Gobitis, Witnesses were subjected to repeated violent attacks. Douglas, Black, Murphy, and Reed began to rethink the question. In Jones v. Opelika, another case involving Witness claims of invaded religious freedom, Douglas, Murphy, and Black announced that they now believed Gobitis to have been wrongly decided. The flag salute issue returned to the Court in 1943, and a majority consisting of recently appointed Robert Jackson, with Douglas, Murphy, Black, and Stone held the pledge requirement unconstitutional. Frankfurter wrote an extremely personal dissent, beginning with the sentence "One who belongs to the most vilified and persecuted minority in history is not likely to be insensible to the freedoms guaranteed by our Constitution."

Frankfurter had joined the Court with the reputation of a champion of civil liberties. However, during most of their common tenure, it was Douglas and Black who took the strong civil libertarian position, while Frankfurter showed persistent deference to elected authority in clashes over individual rights. Nowhere was the difference more clearly displayed than in the prosecutions of members of the Communist Party. Douglas and Black insisted that the convictions violated the First Amendment, while Frankfurter called for judicial subservience to the decisions of the legislature regarding the danger posed by the Party. While Douglas denied it in his autobiography, there is ample evidence to support the widely held view that the Douglas-Frankfurter relationship was exceedingly difficult for most of their shared time on the bench. Douglas was the only member of the Court not to attend Frankfurter's funeral.

Douglas and Black were close both personally and in their constitutional views. They shared antipathy for the practices of the justices who had, in their view, inserted their own political predelictions as barriers to the legislative innovations of the New Deal. with regard to federal authority to regulate the economy, they believed that any activity that substantially affected interstate commerce was within the national government's reach. They both voted to sustain the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which prohibited racial discrimination in public accommodations, such as restaurants and hotels, on the ground that the discrimination itself was a burden on the interstate commerce. While Douglas preferred to support the act under the federal government's power to enforce the equal protection provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment, he had no doubts regarding the adequacy of the commerce power.

As the Court drew back from imposing limits on government power over economic matters, it began to pay closer attention to individual rights claims in matters such as criminal procedure and racial discrimination. In a 1938 case, United States v. Carolene Products Co., Justice Stone said, in a footnote that would become famous, that the Court owed less deference to the other political branches in cases involving Bill of Rights claims, or when the situation involved "discrete and insular minorities" who could not rely on the political process for protection.

The Fourteenth Amendment provides a federal guarantee against state action that deprives people of life, liberty, or property without due process of law, or that denies them equal protection of the laws. The old Court had used the Due Process Clause to impose constraints on state economic regulation, in the name of preserving property rights--constraints that had drawn the fire of the New Deal appointees. Black, particularly, was loath to use the Due Process Clause in this way, because he viewed it as so open-ended as to invite judges simply to substitute their own views for those of the elected representatives of the people. He insisted that the purpose of the Due Process Clause was to impose the specific restraints of the Bill of Rights, originally applicable only to federal actions, on the states, Douglas initially joined him in his view.

Other members of the Court, led by Frankfurter, insisted that the test of due process was what "chocked the conscience" or violated a "concept of ordered liberty." Because not every practice that violated a provision of the Bill of Rights also shocked the conscience or offended the justices' sense of ordered liberty, there were times when Black and Douglas were in vocal dissent.

In similar fashion, Black adopted an "absolutist" approach to the First Amendment's prohibition of laws infringing the freedom of speech and press. For Black the amendment's opening words said it all: "Congress shall make no law"--and this meant "no law." This often put him in sharp dissent from a majority that employed the "clear and present danger test" to weigh the harm likely to follow from the speech against the harm done by suppressing it. In Black's view, the balancing had already been done by the authors of the constitutional provision, and the Court's only task was to enforce their work.

Throughout the '40s, '50s, and early '60s, Black and Douglas could usually be found together on civil liberties issues, sometimes prevailing but often in dissent. In later years they sometimes parted company. Black held to the view that due process included only the guarantees of the Bill of rights; Douglas eventually adopted the position that it could also include some practices that were offensive to liberty even though not mentioned in the first ten amendments. In order to make sense of his absolutist view of the First Amendment, Black had to draw a clear line between speech and other activities that, while communicative, were not speech--such as carrying picket signs. This led him to deny constitutional protection to some activities that Douglas thought were legitimately included.

Douglas was less worried than Black about the coherence and consistency of legal doctrine. He tolerated the disruption of the civil rights protesters of the '60s and '70s, while Black warned that courts and the law were the appropriate path to vindication of civil wrongs. In 1965, Black vigorously dissented from Douglas's opinion in Griswold v. Connecticut, which laid the groundwork for the right to privacy that would provide the foundation for Roe v. Wade, limiting the power of states to regulate abortion. while the two men's friendship endured, their ideological partnership had come to an end.

For much of his career on the bench, Douglas was the object of controversy. Early on, his friendship with President Roosevelt led to speculation that he had political ambitions. that was considered inappropriate by some of his colleagues on the bench, particularly Frankfurter. There is irony in this, considering Frankfurter's own penchant for behind-the-scenes maneuvering in political affairs. But, despite Douglas's own denial of political ambition, it is clear that he was given serious consideration for the Democratic nomination for vice-president in both 1944 and 1948, and he did little to squelch efforts to advance his candidacy. He declined truman's offer of the position in 1948, perhaps because he shared the widespread feeling that Truman as unlikely to be re-elected.

Douglas's personal life was also a source of controversy. He divorced his first wife, Mildred Riddle, in 1953, after twenty-nine years of marriage. Divorce was still an anomaly in American culture. Douglas understood that it would mark the end of any hopes he might harbor for political office. His second marriage to Mercedes Davidson, lasted for ten years. Upon divorcing her in 1963, he married Joan Martin who was twenty-three years old--Forty-two years his junior and eleven years younger than his daughter millie. Three years later Martin and Douglas were divorced, and a few months later he was married to another much younger woman, Cathy Heffernan. That marriage lasted until his death.

More significantly, Douglas was an articulate public voice for political views that, near the end of his career, were becoming increasingly unpopular. His opposition to Communism was always accompanied by attention to the ways in which anti-communist regimes fell short of their own ideals, particularly with regard to their dealings with former colonies. He insisted that the best response to the communist threat was more democracy for the emerging countries, when United States foreign policy seemed to favor manipulation and military control. As his writings on Vietnam suggest, his understanding of the situation on the ground in various parts of the world, informed by his own travels and talks with local people, often put him out of line with the prevailing official position of the U.S. government. Throughout the Vietnam war, he was the one member of the Court willing to entertain claims that the war was unconstitutional because it had not been declared by Congress pursuant to Article I~8 of the Constitution.

Much of this came together in series of threats to impeach Douglas, the most serious of which was led by Congressman Gerald Ford in early 1970. Republican congressmen were upset with the refusal of the Democratically controlled Senate to confirm two successive Supreme Court nominations by President Nixon: Clement Haynsworth, Jr., and G. Harrold Carswell. Douglas's connection with Albert Parvin, a major investor in Las Vegas hotels and casinos, whose charitable foundation Douglas chaired at an annual salary of $12,000, had been under scrutiny and attack for a number of years. In early 1970, Douglas published Points of Rebellion, a short but vigorous attack on the "establishment" which appeared to align him with student anti-war activists. Ford's charges against Douglas included his work for Parvin, characterized as "moonlighting," and referred to a variety of unsavory characters who were associated with Las Vegas, if not directly with either Parvin or Douglas. The charges also referred to Points of Rebellion, described as an "inflammatory volume" in the spirit of "the militant hippie-yippie movement." The impeachment effort ultimately foundered; it was clear that none of the charges against Douglas met the constitutionally prescribed standard of "high crimes or misdemeanors." Democratic control of the Judiciary Committee led to delay of the report of the committee until after the fall election, taking the political pressure off the situation. An exhaustive report by the committee, while not laying to rest all questions about the propriety of some of Douglas's activities, made clear that no impeachable offense had occurred. Douglas understood the attach as entirely political: rather than retire, as he had been considering, and perhaps suggest that there was something to the charges against him, he resolved to stay "until the last hound dog had stopped snapping at my heals."

Douglas suffered a stroke while on vacation in Nassau at the end of 1974. He attempted to return to active service on the Court in the spring of 1975, but the stroke had taken too great a toll, both physically and intellectually. He submitted his resignation in November 1975, having served longer than any other justice in the history of the Court. He died on January 19, 1980.

The writings collected here exhibit the range and power of this most extraordinary man. Lawyer, administrator, judge, civil libertarian, conservationist, student of international affairs, but perhaps most persistently, son of the mountains, prairies, and streams of the Pacific Northwest. From the top of those mountains, one can see a very long way. Douglas saw farther, and deeper, than most.

The identification of William O. Douglas as "Nature's Justice" may seem ironic, since he rejected the perspective of "natural justice' that tended to associate the right with the familiar. But it powerfully underscores the extent to which Douglas was the unique product of the environment in which he grew, with talents and virtues that were fostered in that rugged, stark, and beautiful setting.

The legacy of a Supreme Court justice is problematic. Court opinions often reflect compromises made to secure other votes, and the work of the Court is constantly subject to change. Douglas is probably most clearly identified with the Court led by Chief Justice Earl Warren and, for better or worse, little of this Court's work has escaped revision by later justices. However, Douglas's legacy need not rest on the shifting sands of judicial fashion.

Exploiting the special visibility that comes with a seat on the nation's highest court, Douglas "spoke truth to power," both on and off the bench. His passion was to secure the conditions necessary to human flourishing. In the realm of organize society, that meant the preservation of liberty. He warned that government efficiency is often achieved at a cost to individual liberty. He understood and protested against the moral price that colonizers pay to maintain control their colonies. When it came to the threats supposedly posed by domestic dissenters, including the Communist Party, civil rights protesters, and anti-war activists, Douglas lived by the adage of his friend F.D.R.--"we have nothing to fear but fear itself."

Douglas also maintained a commitment to preserving wilderness, both for its own sake and because it was vital to the human spirit. Part of his legacy is quite visible. The National Historic Park that protects the C&O Canal along the Potomac River is a product of Douglas's leadership, before environmentalism had a name. An unspoiled stretch of Pacific Ocean coastline in the Olympic National Park similarly owes its continued wilderness character to agitation led by him.

A less visible part of his legacy is exemplified by one of my colleagues, a rising young star in the field of environmental law, who spends her summers in the Cascades. Each year while there, she reads Douglas' My Wilderness, drawing inspiration aplenty, not only for environmentalists, but for all concerned to see a world in which liberty, equality, and justice prevail. That is the legacy that justice Douglas--Natures' Justice--would cherish most.