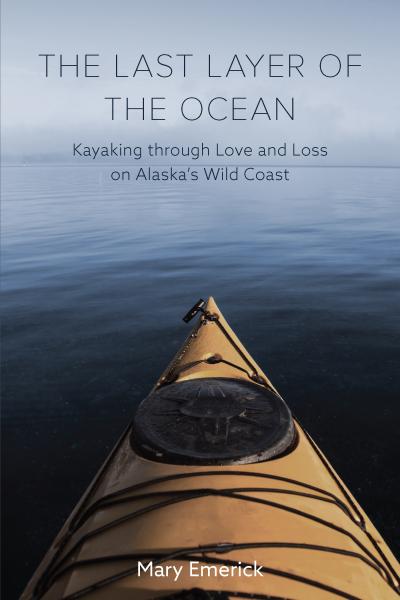

There are five layers of the ocean, though most of us will only ever see one. The deepest layer is the midnight zone, where the only light comes from bioluminescence, created by animals who live there. In order to see, these creatures must create their own light. They move like solitary suns, encased in their own bubbles of freezing water. This is the most remote, unexplored zone on the planet. Though hostile to humans, it’s a source of rapt fascination for Mary Emerick, who would go there in a heartbeat if she could. The Last Layer of the Ocean is a memoir of navigating both a marriage and the stormy Alaskan sea. A woman learns to paddle a small boat and to find her voice in a stark and unforgiving place. In this synopsis, Mary Emerick, takes us on a journey to Southeast Alaska where she describes her self-discovery and the growth it took for her to write The Last Layer of the Ocean.

***

I fell hard and fast for Southeast Alaska when I moved there in 2002. Baranof Island, just one of the many islands that make up the Alexander Archipelago, is a magical place. Shrouded in clouds and mist most days of the year, it was what I needed at thirty-eight years old, when I was trying to figure out the rest of my life. In my job as a kayak wilderness ranger, I paddled far from town into a world that slowly revealed itself as the tide pulled back onto the rocky beaches inch by inch. Everything was hard-won in Southeast Alaska, and that was part of what drew me there.

Still, I wasn’t sure I would write about it. It seemed impossible to explain a place like Southeast Alaska, where life was so close to the raw edge. Bears strolled by in view of our camp; the sea dictated whether we would go or stay. This world was so all-encompassing that it was hard to remember that everyone didn’t live this way. There were weeks, months, when I felt completely cut off from the rest of the country, a curtain of rain closing me in. It was difficult to describe the sense of remoteness and isolation, and the way things could tip in one second: the paddle, set at a slightly different angle, a tip into icy water. People died all the time up there, not from the normal causes you might expect. Instead, it was from falling off mountains, from floatplane crashes, from the random bear in a bad mood.

So, I wrote fiction instead. My first novel, The Geography of Water, was set in a thinly-disguised Baranof Island, and as I spoke at events, the questions were as much about the place as it was about the characters. People were deeply interested in what it was like to live out of a small kayak, fifty miles from the nearest town. I had moved away by then, to a landlocked place that didn’t have the same edge. I missed that wildness, and I realized that I was still haunted by it; it had seeped into my bones the same way rain wormed its way past the barriers I had in place—the dry suits, the rain gear, the survival float coats. I wasn’t done with Southeast, not by a long shot. At a writer’s retreat, where I lived in a dry cabin with an outhouse, I started writing The Last Layer of the Ocean.

I didn’t really want to write another memoir—I had just published one, and memoirs make a writer reach deep. You pull up the guts of who you are from the depths, and this is messy and disturbing and often painful. At the same time, I knew that the way of life I has known there was slowly changing. Politicians are making a run at a different kind of roadless rule for the Tongass National Forest, which could profoundly change the estuaries and bays that I visited. The climate was changing; cedar trees were dying, and we sometimes observed thunderstorms, virtually unknown in the past. More people were coming, with all that implied. Though many have thought that Southeast Alaska will endure, I was not so sure how resilient the landscape could be. I thought people should know about the way it was then, and I wanted to remember it that way too.

As a kayak ranger, I became obsessed with the sea. It was on-the-job training: picking the best line through the rocky shoals, learning how to raft up in the kelp beds so I could stop and read my map, and decipher the tide tables. But what captured my imagination was learning that the ocean had different layers. We had moved through the easy one, the sunlit layer, but there were many others. We had eventually culminated in the deepest one—the place where light would never reach.

What I remember most about kayaking the Southeast Alaskan coast is not the rain that fell in so many forms, dimpling the long, slow swells of the ocean. It isn’t the bears I saw in estuaries, nor the ruins of canneries in long-forgotten bays. What I recall most of all was the drumming of my heart, a beat both of wildness and anticipation. The islands were full of possibility and discovery. Each sweep of my paddle, beads of translucent water dripping from the blade, brought me closer to that elusive place I had always wanted to reach. I had looked for a place to belong all of my life, and I thought this was it. Being out there with just a sliver of fiberglass between me and the deep, unknown layers of the ocean felt substantial and real in a way that no other place had. With each stroke, I felt myself coming alive after a long, hard sleep. No matter that back on shore, my life was in as much of a turmoil as the ocean I paddled through. This, a bright yellow kayak carrying everything I needed was more than enough.

Writing a memoir is largely a selfish act, and my former husband probably would disagree profoundly with how I write about our marriage in The Last Layer of the Ocean. I didn’t want to leave the marriage out because I was figuring out love and kayaking at the same time. Both were difficult in their own ways, and even though I use a plastic boat on a placid lake now, and am married to a very different man, both will always have their hard moments. In the book, I write about the different kayak strokes and how they apply to life. Some strokes are easier than others. Some take a lifetime to learn. In many ways, I am still learning them.

Mary Emerick started a successful kayak ranger program in Southeast Alaska, where she lived for seven years. Prior to becoming a kayak ranger, Mary Emerick traveled around the country fighting wildfires, giving cave tours, planting trees, and conducting wilderness patrols. She is the author of the novel The Geography of Water and Fire in the Heart: A Memoir of Friendship, Loss, and Wildfire. She currently is a wilderness and recreation specialist with the US Forest Service in Northeast Oregon and continues to kayak whenever she can.

Related Titles

The Last Layer of the Ocean

There are five layers of the ocean, though most of us will only ever see one. The deepest layer is the midnight zone, where the...

On the Run

Catherine Doucette is a backcountry skier, horseback rider, and mountaineer—roles that have resulted in adventures where she is often the only woman in a group...